Crandon Park: A Call for Change

Purpose

In 2019, Citizens for Park Improvement approached the landscape architecture firm West 8 to conduct an objective preliminary research and analysis of the Park with the advisory assistance of Charles Birnbaum, founder and CEO of the Cultural Landscape Foundation. The study team sought to answer the following questions:

- What is the current physical and operational condition of Crandon Park?

- How can the Park’s site, facilities and governance be improved?

Process

The study team conducted research between 2019 and 2020, during which West 8 visited the Park and surrounding areas multiple times to document the site using photography, on-site observation, and diagrammatic maps.

In addition, the team studied historical imagery, maps and surveys, previous analytical and environmental reports and master plans. Summation of this research is concluded in this Executive Summary and A Call for Change: Research & Analysis Report (8 volumes).

About Crandon Park

Crandon Park is one of Miami-Dade County’s seven Heritage Parks. It is situated on the barrier island of Key Biscayne and encompasses 975 acres. Visitors access the Park via Rickenbacker Causeway, and then along Crandon Boulevard, which runs through its center.

The Park’s public marina, golf course, beach, cabanas and adjacent picnic areas serve as its primary recreational attractions, while the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Biscayne Nature Center provides educational programs for children and visitors.

Crandon Park’s extensive nature preserves, which exhibit a spectrum of ecologies from upland hammock to mangroves, qualify the Park as a valued environmental asset and a precious habitat for native flora and fauna.

The Park still operates under the guidelines set by the current Master Plan, co-authored by Artemas P. Richardson of The Olmsted Office, Charles W. Pezoldt of Miami-Dade County and Bruce C. Matheson of the Matheson Family.

The History of Crandon Park

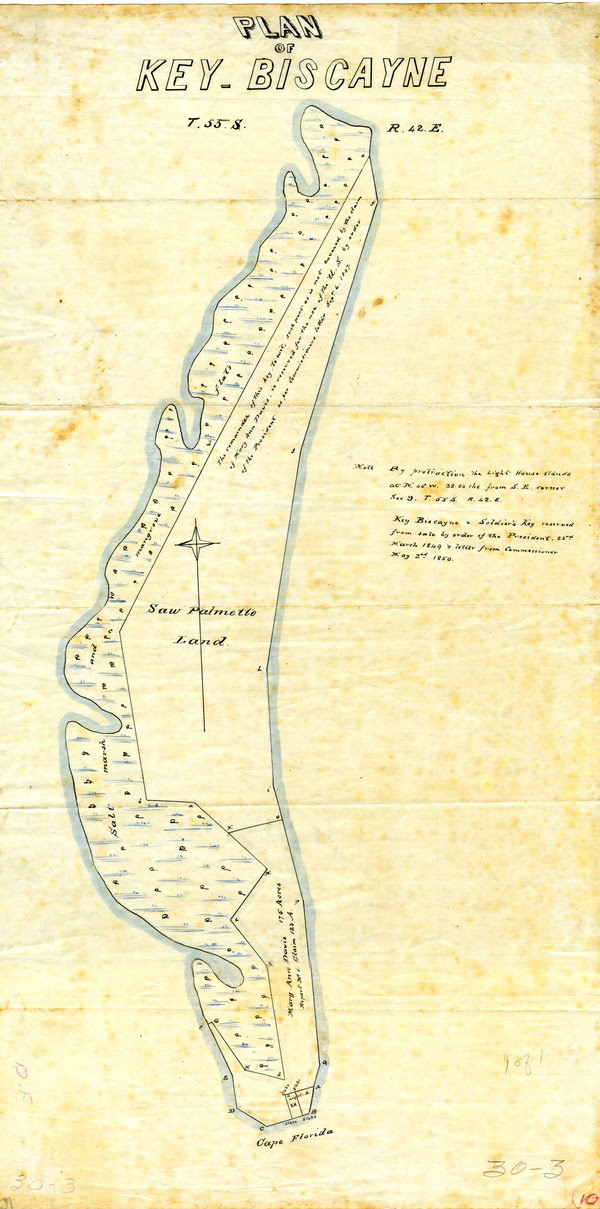

In its early days, Key Biscayne consisted solely of sandy beaches cloaked with thickets of saw palmettos and mangroves. A tribe of indigenous people known as the Tequesta Indians had made Key Biscayne its home for hundreds of years.

Key Biscayne’s eventual evolution into a high-end residential community started in the early 20th century when William J. Matheson, a wealthy industrialist, acquired approximately two thirds of the key. Matheson envisioned a causeway that would link Florida’s mainland to the island, which at the time was accessible only by boat.

The 1940 Matheson deed carried particular conditions that limited the County’s use of the land to “public park purposes” and called for construction of a “roadway extending the causeway entrance to Key Biscayne on the north by a direct route through aforesaid Park Area to the south boundary thereof.”

Renowned today as the pioneer of tropical landscape architecture, William L. Phillips played a major role in shaping Florida’s park landscapes

In 1942 Phillips presented the County with a design for a recreational park that included a beach with cabanas, a park loop stretching along Biscayne Bay, a series of curated view corridors, a central allée, a marina, a canoe club, camping grounds, as well as various play fields for horseback riding, tennis and golf.

Crandon Park officially opened to the public in 1947. Phillips later designed the grounds of Crandon Zoo – now Crandon Gardens – with lion tamer Julia Allen Fields. At its peak popularity in the mid-1970s, Crandon Park was attracting nearly two million visitors annually.

Master Plan Evolution

The need for a master plan was first identified in an interdisciplinary study called Crandon Park: The Next Fifty Years. The study pinpointed many issues that persist today.

Miami-Dade and the Matheson family agreed to a number of covenants which restricted flexibility in the location, footprint, size, and functions of Park facilities.

Crandon Park’s Master Plan document was created through an atypical process that was by and large conducted without significant public input. As a result the Park has not been able to adequately serve the diverse need of its constituents.

The current Crandon Park Master Plan is the result of three major revisions. Many of the current Master Plan recommendations were never realized, such as the inclusion of nature trails through the preserves, enhancement of the beach dunes, opportunities for flexible recreational fields, diversified bike and pedestrian circulation, and improved access across Crandon Boulevard. Such solutions would have helped minimize today’s friction between cars and pedestrians/bicyclists.

Shackled to outdated policies, Crandon Park has become “frozen” in time. The current Master Plan is so restrictive that it essentially locks in time, what existed in 1995 and not only limits change, but promotes resistance to change.

The Master Plan

Crandon Park’s Master Plan document was created through an atypical process that was by and large conducted without significant public input. As a result the Park has not been able to adequately serve the diverse need of its constituents.

Miami-Dade County and the Matheson family agreed to a number of covenants which restricted flexibility in the location, footprint, size, and functions of Park facilities.

Many of the current Master Plan recommendations were never realized, such as the inclusion of nature trails through the preserves, enhancement of beach dunes, opportunities for flexible recreational fields, diversified bike and pedestrian circulation, and improved access across Crandon Boulevard.

Six Key Challenges & Constraints

Crandon Park needs to unify its mixed identity.

Crandon Boulevard bisects the overall venue both visually and spatially. The Park must focus more heavily on building a unitary and unified identity. It must deliver a uniform and consistent level of maintenance throughout the entire property. The Park requires far greater uniformity in respect to furnishing styles and lighting elements. It also suffers from poor signage visibility, which further weakens its ability to project a uniform identity.

An excessively rigid planning framework stymies fundamental modernations.

The current Crandon Park Master Plan contains restrictive covenants that impose excessive levels of inflexibility in managing the Park’s growth, in the maintenance of its facilities, structures and signage, and in the management of invasive, endangered or threatened species and vegetation overgrowth.

Crandon Park is underutilized and burdened by weaknesses relating to operations, management and revenue.

Preliminary on-site observation and an overview of the operational hours of the Park’s concession stands, Crandon Gardens, the Tennis Center and Calusa Park clearly demonstrate that the Park is underutilized, particularly on weekdays. The Park is not optimizing its potential revenue sources. It must provide opportunities for more inclusive, community-oriented stewardship – and for broader and more balanced sources of revenue.

The Park is vulnerable to sea level rise and hurricane events.

Because of its low elevation and flat topography, Crandon Park has always been vulnerable to hurricanes, storm surges, and, increasingly, sea level rise. The Park appears to lack a strategy to address these urgent concerns. Moreover, none of its facilities or program areas appear to be equipped with proper resilience-promoting features. Crandon Park’s eroding coastline and dune system pose risks to its survival. Although some measures were implemented in the early 1990s to stabilize Crandon Park’s coastline and beaches, many of its natural assets are still heavily vulnerable to erosion. Experts have recommended dune protection and enhancement since the Crandon Park: The Next Fifty Years report in 1989, but these were never implemented.

Crandon Park suffers from poor accessibility and poor circulation.

The Park focuses too heavily on the automobile. Its circulation and access are confusing and, to an extent, dangerous to cyclists and pedestrians. There is limited access and connectivity among its various Specific Areas (e.g., Marina, Beach, Golf Course, Bear Cut Preserve, etc.).

The Park suffers from poor maintenance.

A number of facilities are either severely damaged, abandoned, or inaccessible to the public because of plant overgrowth. Many of the preserves seem to suffer from invasive species growth and such basic maintenance problems as broken fences. The West Point and Ibis Preserves are not accessible to the public even for passive nature observation activities, as recommended in the current Crandon Park Master Plan.

Crandon Park Recommendations

Crandon Park possesses the potential to stand as a model of coastal resilience – and as a world-class beach park and preserve. It is large enough to serve many diverse park functions and activities. A quiet refuge. A place to explore unique natural habitats and learn about local native flora and fauna. A gathering space for a family picnic or group celebrations. A place to relax and swim from a beautiful beach. A well-managed and developed marina to provide public access to the ocean and bay. And, the highest level of recreational golf, tennis and other sports favored by the County’s diverse community.

- Reassess the best ways to accommodate current visitorship and parking capacities. Reconfigures vehicular circulation to reduce bottlenecking at the entrance.

- Generate revenue to support Park maintenance by hosting cultural and social programming or events at the Marina.

- Revise the Master Plan’s restrictions on building growth and development to meet current visitorship needs.

- Create a maintenance plan for the vegetative overgrowth and invasive species along Crandon Boulevard and restore its former “Causeway” character, as reflected in Phillips’ Vision Plan.

- Reconfigure the road and its access points to minimize the conflict among cars, bicyclists, and pedestrians.

- Explore options to address sea level rise and storm surges, such as raising the road, improving on-site water management, or other grade change/topographical measures.

- Per a recommendation appearing in Richardson’s 1993 iteration of the Master Plan, consider construction of a vehicular bridge along Crandon Boulevard with a pedestrian/cyclist underpass connecting the Central Allée and lagoon.

- Work with an Environmental Consultant to create a management plan for trimming overgrowth and invasive flora and fauna

- Introduce nature trails with minimal impact on existing wetlands – per Master Plan recommendation – and add guided tours by trained naturalists, as well as interpretive signage, to help educate Park visitors.

- Study various scenarios that would protect the Golf Course from storm surges and sea level rise.

- Where possible, fairways and recreational green areas should be elevated so they are protected – and so golfers can enjoy unobstructed views of the City of Miami and Biscayne Bay above the shoreline mangroves

- Consolidate the Clubhouse and its facilities closer to Crandon Boulevard to provide users with easier pedestrian and bicycle access. Explore potential to share parking with the North and South Parking Lots.

- Future updates to the Course should improve the tidal waters, employ best practices to reduce the amount of mowed open lawn, use salt-tolerant grasses, and implement contemporary stormwater retention techniques.

- Remove of repurpose the large stadium structure

- Reassess the Tennis Center layout to be more suitable for recreational tennis (or other recreational uses), rather than the current arrangement placed to accommodate a professional tournament.

- Consideration should be given in connection to renovation of the golf course and tennis facility to a common golf/tennis clubhouse, pro shop and locker room facility to serve both recreational venues adjacent to Crandon Boulevard, eliminating acres of asphalt.

- Introduce nature trails and informative signage with minimal impact on teh existing wetlands and sensitive environs, per present-day master Plan recommendations. Boardwalk trails could help reduce the impact of foot traffic on sensitive undergrowth.

- Facilitate guided tours by trained naturalists to educate Park visitors.

- Manage dangerous overgrowth and invasive species.

- Create natural waterways for Park visitors to take non-motorized watercraft – including kayaks and water paddles – for exploring the Park’s wetlands.

- A revised master plan should consider the viability of this site for any recreational use due to its vulnerability to flooding.

- If the facility has a future in light of the elevation of the land, work with the Village of Key Biscayne to identify suitable types of programming that would best fit the community’s and park visitors’ needs.

- Create a park maintenance plan to manage invasive species, vegetative overgrowth and trail safety. As a point of comparison, the Bill Baggs Florida State Park revises its ongoing maintenance plan every ten years.

- Post additional educational signage to help visitors learn about the ecology and landscape.

- Allow the Nature Center to expand to meet the needs of the community and facilitate its educational mission to help visitors learn about the Park’s unique fossilized reef, coastal ecology and rich history.

- Enhance the beach dunes for resiliency, and stabilize the shoreline.

- Improve concession stands and food service to attract visitors throughout the week. This source of revenue can help fund Park maintenance.

- Reopen the view corridor near the lagoon to the Biscayne Bay, restoring Phillips’ desired physical and visual connection between the eastern and western sides of the Park.

- Reduce impervious surfaces and apply resilient materials and permeable pavement.

- Reduce or innovatively reimagine parking configurations to fit today’s usership, based on current traffic analysis.

- Fluidly integrate the parking lots with the Picnic Grounds, which would reflect a 1995 Master Plan recommendation to create zones for flexible, active recreation.

- Upgrade the cabana facilities and adjust their usership as needed.

- Remove and re-landscape the cabana road or at least reconsider its function and purpose.

- Create tailored and adaptable creative art programming at Crandon Gardens that reflects community needs and interest.

- Create a coherent circulation and garden layout that takes into account both visitor and community interests.

- Upgrade the existing relics to make them safe and attractive.

- Increase and promote public awareness through educational signage and/or tours of these valuable historic sites. Educate the public about their relation to Crandon Park’s rich history.

One Crandon | Phase 2

Citizens for Park Improvement has retained West 8 to complete the second half of its Crandon Park planning. Its scope of work includes development of a new comprehensive master plan for the Park and proposals, a redesign of both the east and west park properties and an evaluation of the cost of each element of the plan.

Prior to submitting a proposed plan to the County and the Crandon Park Master Plan Amendment Committee, CPI will identify major donors to fund each element of the park improvements with the caveat that the park is not to be commercialized, made more expensive that it is for access and use, or lose its character as a public park.

That is, donors must necessarily be purely philanthropic.